Cross Seam Swing - New Variations in the New World?

With the World Cup in the USA and West Indies, what can we learn from baseball aerodynamics to help bowlers uncover new skills?

“I’m not sure if any other sport has that feeling - first ball, in and out of the game. Your day is done, right when it starts” - Jimmy O’Brien, India vs Pakistan

The 2024 Men’s T20 World Cup has been an odd affair so far. Tropical storms, pop-up cricket stadia, and excitable baseball commentators have given the opening few weeks a different flair compared to a typical ICC event.

Already we’ve had several upsets, with the hosts USA beating Pakistan, and serial semi-finalists New Zealand crashing out in the group stages. The India vs Pakistan match, always the biggest event in cricket, was dampened by a tough batting surface and more than a handful of empty seats.

A highlight for me has been some of the ‘Baseball vs Cricket’ discourse happening online, as fans start to compare the two sports. Jimmy ‘Jomboy’ O’Brien, a popular baseball content creator, has featured on the TV commentary, and has brought interesting, informed local insight to the discussions.

All of this provides the perfect opportunity to delve into a topic I’ve been interested in for a while: the fascinating links between cricket and baseball aerodynamics, and what can be learned from our American sporting counterparts.

Cross seam deliveries…that swing?

As you will guess from the title, this post is about cross seam bowling, something usually reserved for misty-eyed reminiscing about Liam Plunkett’s 2019 World Cup campaign, and definitely not fit for polite, dinner-time discussions of swing bowling.

For context, a cross-seam delivery is one where the ball rotates ‘over the seam’, rather than ‘around the seam’. The latter is how swing is taught: rip your fingers down the ball for backspin while presenting an upright, stable seam to get the ball to swing. Cue footage of Jimmy Anderson bowling which makes everyone feel warm and fuzzy inside.

But what if, in this age of wobble seam bowling, there was a way to bypass all the effort of shining a ball and honing perfect seam presentation, so that instead, you could swing a cross seam delivery? Roll the clip (copyright Sky Sports).

“That looked like it, sort of, shaped away slightly for a cross seamer” - Steve Smith on commentary

I noticed this delivery thanks to Steve Smith’s commentary, and was then able to study it in more detail as the slow-motion replay was shown in the broadcast. It might be hard to distinguish from the footage, especially as the ball also moves off the pitch, but it does shape away as a cross seam delivery. Not a lot, but about a third as much swing as we expect to see with a new ball.

So what is going on here? There is no shiny side, no seam position, no side spin, but the ball moves sideways in the air. The answer, believe it or not, can be found when we dive into the secrets of baseball pitching.

‘Seam Shifted Wake’ pitches

Now I’m not going to assume any of you are baseball aficionados, I, for one, am certainly not. But I do hope that you can appreciate the general similarities between a baseball pitch, and a cricket delivery.

While a cricket ball is delivered overarm, a baseball pitch is more side on, a bit like the classic southern hemisphere throwing action. This allows fast pitchers to impart side spin on the ball, similar to a football free-kick, or a slice in golf, which makes the ball curve in the air. These ‘curveballs’ occur due to the Magnus Effect on a spinning body, and can be reproduced with any spherical object, made with seams or otherwise.

For years, people thought that spinning the ball was the only way to move a baseball in the air. Spin it sideways, it moves sideways. Apply topspin, and it dips. You get the gist.

However, the work of some very smart aerodynamicists, coupled with novel data from ball-tracking company Hawkeye, shows that the seam on a baseball plays an important role, just as it does in cricket.

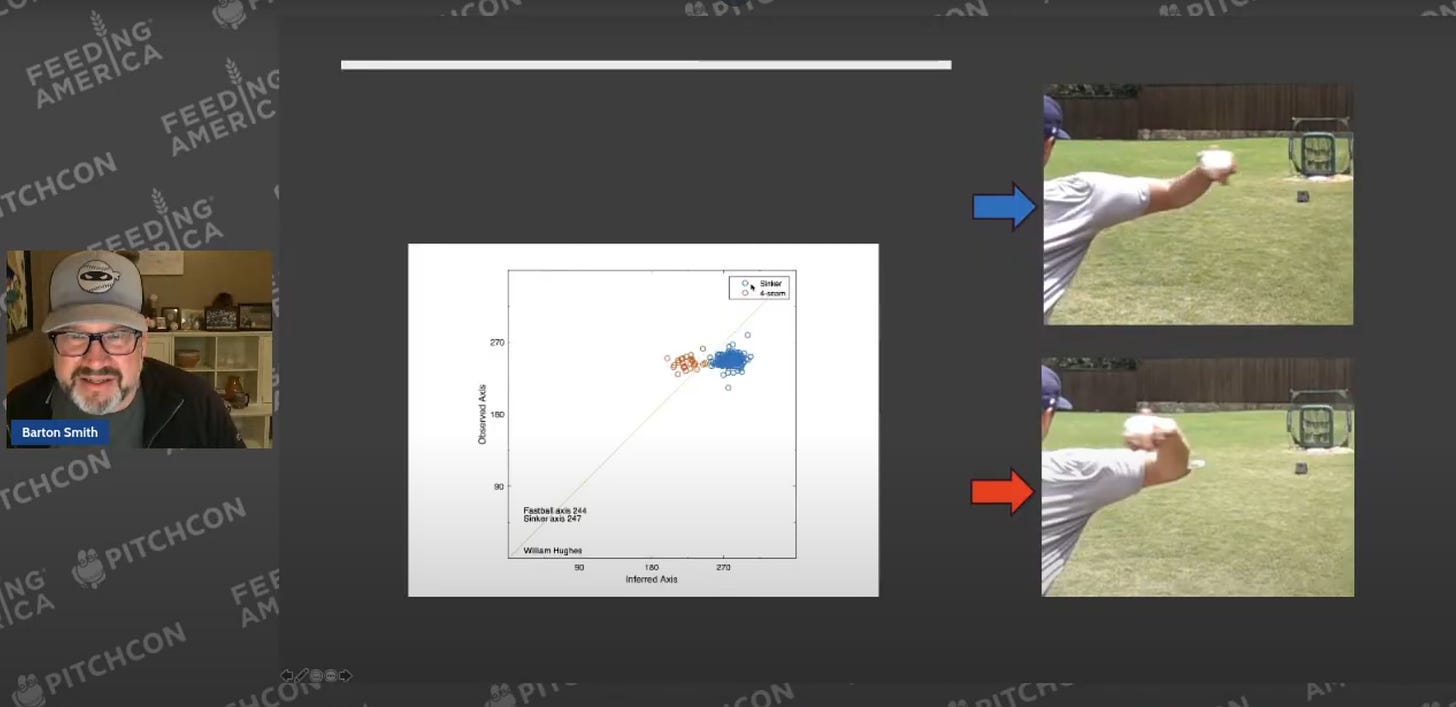

For those of you interested to learn more, I highly recommend Barton Smith’s blog on the aerodynamics of baseball, where he does a great job of explaining this fascinating topic in detail. For now, I shall link more of his work, and try to summarise the ideas found in their publications (seriously, go read, listen to, and watch it all, it is brilliant).

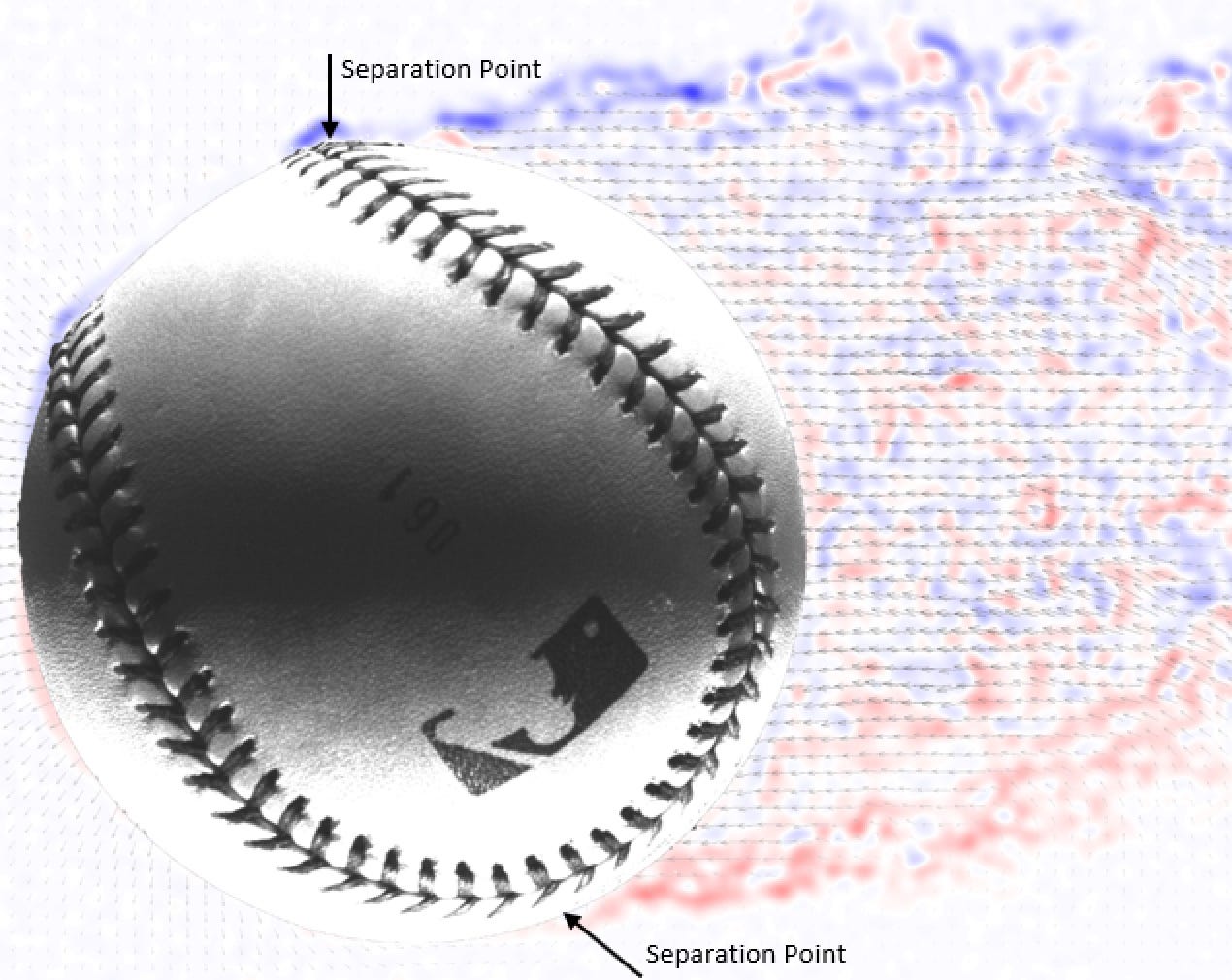

This leads us to the concept of a ‘Seam Shifted Wake’ pitch: if a baseball spins just right, the seams can shift the separation points of the boundary layer on the ball. This creates asymmetric flow in a different direction to the Magnus Effect set up by the spin. This is very similar to swing in cricket, where a ball moves sideways while the ball rotates with backspin.

In cricket, bowlers change the boundary layer profile on either side of the ball, using the seam at the front of the ball, along with surface condition. A Seam Shifted Wake pitch works when the boundary layer separates as it encounters the seam towards the back half of the ball. I’ll skip over the technical ways you get a baseball pitch to do this, but you can see the result in the figure below from the Smith and Smith’s research paper.

So how does all of this relate to Siraj’s delivery in the game against Pakistan? Well, let’s go back and look at what the seam was doing in more detail.

The ‘fixed points’ of a cross seam delivery

To work out the similarities between the Siraj delivery and a Seam Shifted Wake pitch, we need to break down the orientation of the ball, frame by frame. Below are some stills taken from the footage, moving left to right in time.

We can see in each snapshot that there is a point on the left-hand side of the ball where the seam is always present. Let’s call this a seam fixed point; I’ve highlighted this spot with a red circle.

As the ball is rotating around this point, there must also be a fixed spot on the opposite side of the ball, like the north and south poles on the Earth. Therefore, even though the ball is spinning, the seam is always present in a fixed position on the back-left and front-right of the ball.

Applying the logic from Seam Shifted Wake pitches, the boundary layer is likely to separate close to these fixed seam points. This means that we have separations behind the midpoint on the left side and in front of the midpoint on the right side.

We know that conventional swing happens due to separation asymmetry on either side of the ball; the cross seam on Siraj’s delivery creates a similar type of airflow around the ball, deflecting the wake to the right and causing the ball to ‘swing’ slightly to the left. This is cool because it doesn’t require a shiny side, or a stable seam position to get movement in the air! Instead, the cross seam delivery with a slight angle uses seam ‘fixed points’ to shape the air.

While we don’t see as much movement as we do with conventional swing, this technique may unlock lateral movement for fast bowlers when swing is otherwise hard to achieve, for example with an old ball.

This also works for spin bowlers!

Spin bowlers also move the ball in the air, and for the best of the best, it is a key weapon in their arsenal. Shane Warne’s ‘Ball Of The Century’ was so deadly because it combined drift into the right-handed Mike Gatting, with sharp turn in the opposite direction. Sit back and enjoy:

I think it is fair to say that the aerodynamics of spin bowling is less well understood than swing, but it is super interesting, and has a lot of overlap with baseball pitching. A deeper dive into the way that spin bowlers move the ball in the air is on my to-do list, but for now I’ll leave you with some initial thoughts to round this post off.

When you look at the ball-tracking data for spin bowlers, two different groups begin to emerge:

Those who drift the ball in the opposite direction to the direction of turn (like Shane Warne above)

Those who drift the ball in the same direction as the direction of turn

My theory is that these groups stem from the two different aerodynamic mechanisms: spin-dominated drift vs seam-dominated drift.

The first group utilises the Magnus Effect, as described earlier, using the rotation of the ball to generate sideways movement in the air. The second group uses the orientation of the seam to shift the boundary layer separations, and generate drift, just like a Seam Shifted Wake pitch in baseball, or the cross seam swing delivery above.

These ideas need more thought and research, and more words to flesh out the idea than I am planning to write today! However, next time you watch a spin bowler in action, think about the orientation of the seam and direction of rotation, and how these might be making the ball move in the air.

That’s all for me, I hope everyone is looking forward to the knockout stages of the World Cup, especially after England’s great escape from the group and awesome result against the Windies last night! If you’ve seen anything interesting on the cricket coverage lately, whether swing or spin related, feel free to get in touch, as I’m always looking for new ideas to delve into. Go well!

Who are the spinners who have drifted in the direction of spin?